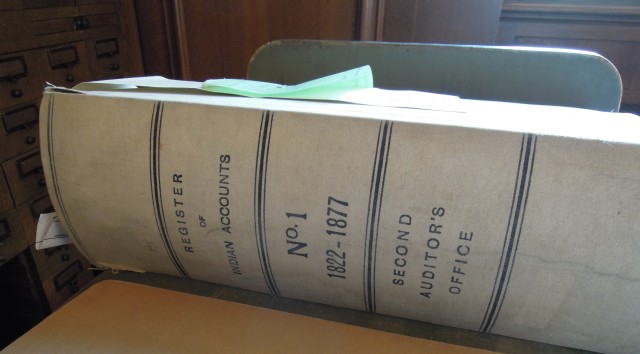

It’s easy to imagine why Record Group 217 has been obscure. The nondescript name, “Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury,” promises little more glamorous than 19th-century auditors’ records. As the target of research, RG 217 is a last-picked-child on the scholarly playground at the National Archives.

Today, RG 217 is on a fast track to becoming one of the hottest, underused records groups at NARA. Scholars love new primary sources. Since 2013, sometimes researchers wait their turn in the Reading Room to look at some boxes of RG 217 records. Given the funding and time, who wouldn’t like to go sleuthing on a story dated between 1775 and 1927 to see what history has forgotten?

Thanks to the grants of generous donors administered by the Minnesota Independent Scholars’ Forum, I have been fortunate to conduct four research forays into RG 217 to identify new primary sources about Federal interactions with Dakota people in Minnesota in the 19th century.

The shelving required to house RG 217 is so extensive that it wraps from the West to the East sides of the stacks at Archives 1 in Washington D.C. Removed from the stacks, the collection would cover three-quarters of a football field to a depth of one foot.

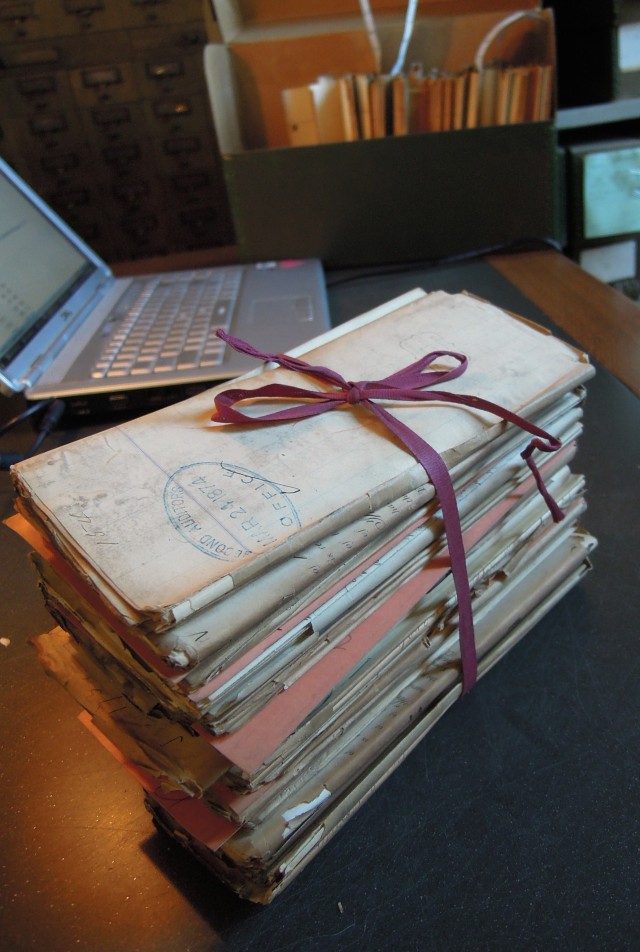

Although the documents date to 1863, the red tape and Hollinger box are artifacts of 1995, the last time this section of RG 217 was processed by National Archives. The author, NARA, May 2014.

See the Table of Contents in the RG 217 link above to overview the entire collection.

Scholars have largely overlooked RG 217, not understanding how it was created or what it contains. In the late 18th, the 19th and the early 20th centuries, the Congressionally-mandated Treasury auditing process categorically removed documents from Federal agencies like the Office of Indian Affairs.

Records that did not require auditing –the vast majority, like letters received and sent, reports, maps, treaties — remained in the Indian Office. Today, these documents are staples of scholarly research on Federal relations with Indian Nations in America, collected as National Archives RG 75, Records of the Office of Indian Affairs. Like many Record Groups at NARA, it has earned a reputation for divulging fascinating new information scholars are not looking for while keeping mum on subjects of intense interest.

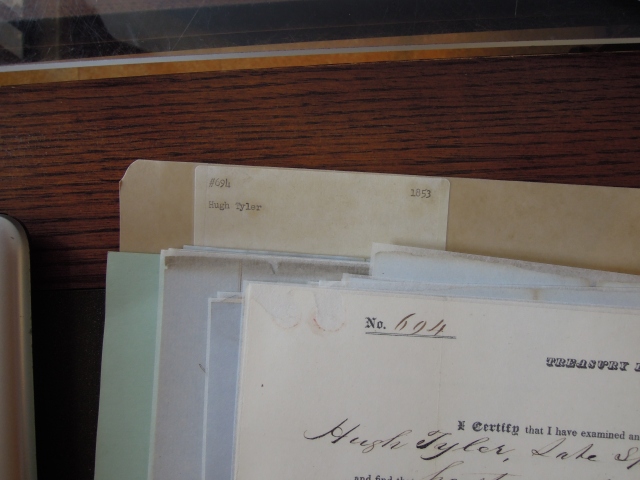

Take the subject of Hugh Tyler. Students of Minnesota history know Tyler as a political friend of Alexander Ramsey, hired on as Commissary for the Treaties at Travers des Sioux and Mendota in 1851. We know little about Tyler apart from allegations made by a political rival, Madison Sweetser. In the wake of those Treaties. Sweetser alleged Tyler and Ramsey colluded to pass money under the table to their trader-cronies, money that rightly belonged to Dakota people.

A Congressional investigation exonerated Ramsey in 1854. William Watts Folwell, Minnesota’s first historian to assess the scandal, was dubious about the Senate findings.(1) As Rhoda R. Gilman summarized Folwell’s argument, “No record was kept of Tyler’s activities. But his expenses [reimbursed by Ramsey from Indian Affairs funds] were considerable.”(2)

It turns out that Hugh Tyler’s records were retained. Modern scholars can examine Tyler’s activities during the negotiations of the 1851 Treaties –as well as Madison Sweetser’s and Alexander Ramsey’s settled accounts. (3) The records Folwell lamented as missing had been transferred from the Office of Indian Affairs to the Treasury for auditing. They are now located in RG 217.

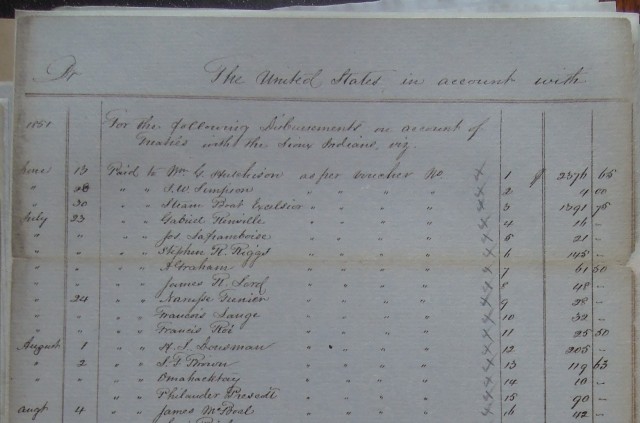

Hugh Tyler’s account covering Treaties made in Minnesota in 1851, settled in 1853. RG 217 NARA.

Documents like this list in Hugh Tyler’s Account No. 694 were created as an employee of the Office of Indian Affairs and transmitted to it for reporting. The OIA forwarded these documents to the Second Auditor of the Treasury for settlement. This detail from a ledger sheet shows the names of people Tyler hired (including a Steam Boat, a missionary, a number of French-Dakota men and others associated with the fur trade), the date and amounts they were paid, and Auditor’s marks indicating the file contains a Voucher (receipt) signed by each person.

Settled accounts were permanently collected at the Treasury, where the records backed up the work of the last people to handle them: auditors. The documents were not returned to the Federal offices that generated them. When NARA opened in 1935, it followed the archival practice of preserving the provenance of the collections it accessioned. That meant that records that came into the National Archives from the Treasury retained the order and identifiers assigned to them there, further obscuring the origin of these records outside the Treasury Department.

For example, Tyler’s account from the Treaty of 1851 is not filed by that year, where a scholar would expect to find it in RG 75. Rather, it is filed in RG 217 among other accounts settled in 1853, the year the auditor closed Tyler’s case.

In this way, the historically invisible auditing process removed data-rich primary sources out of the NARA records collections scholars routinely consult. At the Treasury, some accounts were further removed by the time that passed before settlement. In the cases I have surveyed, an account may have been settled, and therefore was filed, from one to thirty-two years after the events captured in the file.

Institutional collections policies follow scholarly demand. We can’t be interested in records we don’t know exist.

But now we do. It is no coincidence that RG 217, among other newly discovered collections at NARA, is coming to light now. Digitization and the application of big data to history mean we have the tools at hand to mine these records for new stories and to update ones we think we know –tools that Folwell never dreamed of when he tried and failed to locate these records a century ago.

__________________________

(1) William Watts Folwell A History of Minnesota Vol. 1, The Minnesota Historical Society. Press, 1921. p. 290-293.

(2) Rhoda R. Gilman, Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart, The Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004, p. 131 and Mary Lethert Wingerd, quoting Gilman quoting Follwell in North Country: The Making of Minnesota, The University of Minnesota Press 2010, p. 383 n 31.

(3) Ramsey’s accounts from the Treaty are curiously misfiled in RG 217. If this anomaly is an artifact of the period settlement process, some accounts available to scholars today may not have been available during the Ramsey investigation.