This post is a classic exercise in doing history. The file of leads appears to be straight-forward. But upon a close reading of the texts, we are left to wonder.

Captain John S. Marsh of the 5th Minnesota Volunteers, Company B has always been a mystery to me. Was he “gallant” or “misguided” for marching boldly out of Fort Ridgely the morning of August 18, 1862, to put down the rumored unrest at the Lower Sioux Agency? Marsh was an officer with front-line experience at Bull Run in Virginia. But to hear the story survivors told, Marsh brushed off every caution urged by settlers fleeing the Agency and marched half his command to their deaths in a Dakota ambush at Redwood Ferry.

No one has adequately explained what Marsh was doing at the time he drowned, hours later while trying to cross the Minnesota River toward the Lower Reservation. Other survivors headed the opposite direction, toward Fort Ridgely. Folwell explained that after the ambush, Marsh and some of his men retreated under cover of the brushy tree-line on the north bank of the river until,

“At length a point was reached where the cover was too thin. Captain Marsh decided to cross the stream, thus escaping the Indians’ fire, and make his way toward the fort along the south bank. He would not have so resolved had he known or, if knowing he had reflected that he would find himself in one of the Sioux villages.” [1]

The monument in the Fort Ridgely Cemetery marking the graves of the soldiers killed at Redwood Ferry August 18, 1862.

I make no claim to solving the mystery of Marsh’s deadly bravado. But the story is complicated by a source suggesting that while stationed at Fort Ridgely, John S. Marsh had allied himself with a Dakota band via kinship: that he had a relationship with a Dakota woman who, it is said, was carrying Marsh’s child the day Marsh died.

Evidence is scattered and insubstantial enough to leave me wondering, not convinced. But I share the sources, thin as they are, to underline the point that the questions I have raised in this series about relationships between army officers and Dakota women are not esoteric. These were real relationships between real men and women. Some of those relationships resulted in the births of real children. All the actors played real, if unrecognized, roles in the real-life drama we call ‘history.’

We’ve already seen the context of John S. Marsh’s story. Eli Huggins agreed with Stephen Riggs’s assessment that it was “exceedingly common” for military officers stationed on the frontier to have a temporary relationship with a Native American woman. Huggins said the exceptions were, sometimes, married men and missionaries. Marsh was not married and his religious affiliation, if he had one, is unknown.

Further, now that we are beginning to understand the privileges accorded post commanders –like importing slaves to Free states and territories as servants –I better understand why temporarily taking a Native sexual partner was viewed as ordinary. Like slaveholding, it wasn’t something every officer would choose to do. But few would view it amiss if he did.

Listen to how nonchalantly Timothy J. Sheehan recorded this in his diary while his detachment was stationed at Yellow Medicine the summer of 1862:

July 13: “All quiet in camp lots inds. prowling around about 2000 bucks squaws and papooses danced in front of the traders stores called it the great buffalo dance squaws had on buffalo robes all painted one young squaw wore around her the stars and stripes wanted to marry white man Mark Greer took her to teopie [sic] stayed all day.” [2 ]

*****

“Nancy McClure, or Winona” by Frank B. Mayer, 1851. MHS

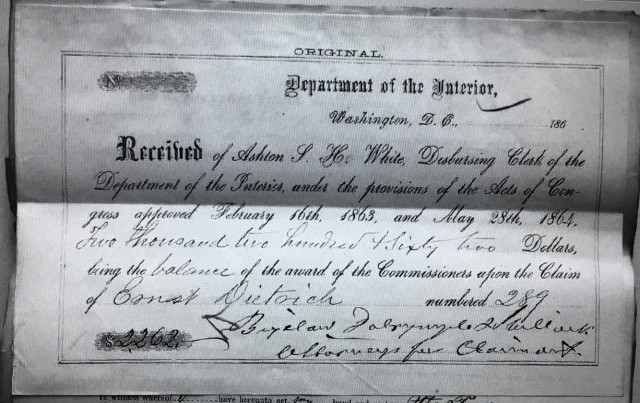

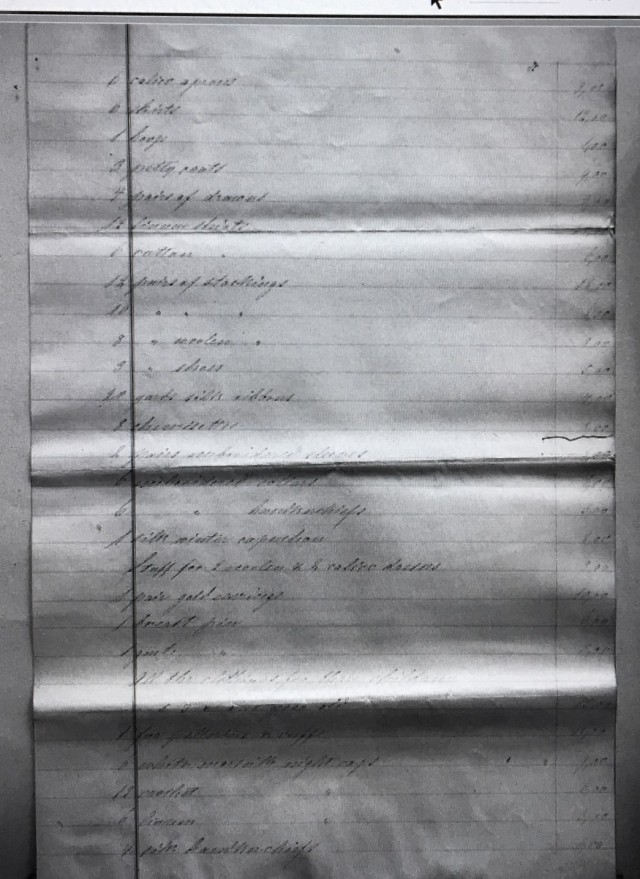

The earliest documentation of the Marsh-baby allegation comes from Nancy McClure. Ironically, McClure (1836-1927) was the daughter of a Dakota woman, Winona, and an army officer stationed at Fort Snelling, James McClure. When she was in her eighties, McClure told Mankato historian Thomas Hughes,

“Sleepy Eyes had two grandchildren living in Canada. One was called Her Cloud, who had a son by a volunteer officer at Fort Ridgely — I think the officer’s name was Marsh. Her Cloud during the outbreak fled to Canada and her son grew up there and has a big farm near Pipestone, Canada. Her Cloud died a few years ago.” [3]

Hughes’s co-author, William C. Brown, marked Marsh’s name to be stricken from the manuscript in which the quote appears, Old Traverse des Sioux. Commenting on a galley copy Hughes sent Brown for proofing, on March 24, 1928, Brown told Hughes to strike ” ‘–I think the officer’s name was Marsh’… as Heitman’s Register does not show any regular army officer named Marsh who could possibly have ever served at Fort Ridgely.”

On March 26, 1928, Hughes replied to Brown,

“In regard to Captain Marsh commanding at Fort Ridgely, would say that he was not a United States Officer at all in the sense of belonging to the regular army. There was not one soldier at Fort Ridgely for over a year before the Outbreak that had enlisted in the regular Army, but they belonged to the Fifth and Sixth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry….all the regular U.S. soldiers had been sent south. Captain Marsh belonged to the Sixth Minnesota Infantry and was the officer in command at Fort Ridgely at the time of the Outbreak and was crowned in the Minnesota River… he had been in command at Fort Ridgely for six months or more, and he is the officer I presume that Mrs. Huggins referred to, in fact she told me so, as being the father of ‘Her Cloud.'” [4]

Hughes’s claim is typical of written documentary history: a mixed bag of ‘facts.’ It is unfortunately easy to parse out the piece that supports a hypothesis –let’s say the affirmative ‘she told me so’ here– and declare, positively, that McClure said Marsh had fathered a Dakota baby. In fact, that is essentially how Hughes himself used McClure’s story: read it to confirm his belief that Marsh had a Dakota child.

But listen to how an attorney might cross-examine Hughes if, instead of publishing this vignette, he had spoken it as oral testimony in court.

“Which is it Mr. Hughes? Did Mrs. McClure actually name Marsh, or did you ‘presume’ she was referring to Marsh and you supplied his name?”

No matter how Hughes answered, the follow-up questions would have gone hard for him.

“Can be you be certain of that, Mr. Hughes? Did you say Marsh was Captain in the Sixth Regiment?”

“Yes, I did.”

“But he was in the Fifth, Mr. Hughes. Perhaps you’ve forgotten? How about “Her Cloud”? You have stated both that she was the mother of Marsh’s baby and that Marsh was Her Cloud’s father. Which is it?”

There’s also the big problem of Hughes’s claim in Old Traverse des Sioux that he obtained Nancy McClure’s story (Chapter X) when she visited St. Peter, while much of the content –although not the Marsh passage –is lifted verbatim from letters McClure wrote to historian Return I. Holcombe, three decades before she visited Hughes. [5]

Parsing history is devilish, isn’t it? Even though we might judge Hughes an unreliable transmitter of McClure’s story, the fact remains that McClure is a reliable source. Her own mother had been in Her Cloud’s position and McClure herself was a living parallel to Marsh’s baby. So we can expect the story might have had unusual staying power for McClure.

Further, in 1862, during the months Marsh was stationed at Fort Ridgely, McClure was living with her husband, David Faribault Sr., on the government road that connected Ridgely and the Lower Sioux Agency, crossing the Minnesota River at Redwood Ferry. If Marsh had a relationship with a woman on the reservation side of the river, Marsh would have passed Nancy McClure’s front door coming and going (unless he crossed the river at the Ridgely ferry).

There is also a body of evidence, larger than I will present here, supporting the idea that during the summer of 1862, Dakota men cultivated an alliance with Marsh designed to safeguard Dakota autonomy during the pending 1862 annuity payment –autonomy undermined in past years when Ridgely commanders had supported the Indian Agent’s agenda.

If Marsh had entered into a relationship with a Dakota woman, might not that have opened a door for her kin to expect Marsh would at least hear their grievances against the government, and perhaps help Dakotas balance the scales in 1862? Former Sioux Agent Joseph R. Brown complained to Ignatius Donnelly in 1865,

“I think in a former letter I shared that all intercourse with the Indians should be through the Agent and all military officers should be forbidden from counseling or in any manner interfering with the Indians except upon the application of the Agent….

At Fort Snelling the Agent suffered many indignities through the usurpation of powers by the Comdg. officer in connection with the duties of the Agent; and I am satisfied that the germ of dissatisfaction on the part of the Lower Sioux was brought forth by the interference of the Comdg. officers for a period of three or four years at Fort Ridgely. Poor Captain Marsh whose life was sacrificed at the Lower Agency went so far as to counsel the Indians in case the Agent should attempt to retain any of their annuity money on account of depredations, to take it from the Agent by force, and to refuse to payment of all debts to traders and that his troops would protect them in doing so.” [6]

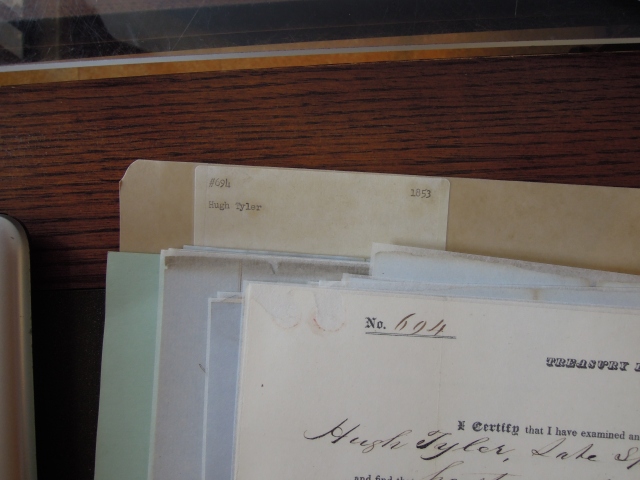

The final scrap of evidence in my Marsh file was unearthed by Corinne L. Monjeau-Marz while she was transcribing primary sources for her book, The Dakota Internment at Fort Snelling 1862-64. In the Catholic Church of St. Peter [Mendota, MN] Parish Baptismal Register, Marz found an entry for baby Julius Gere, born to Wakinyaniwin and a man surnamed Gere, given name not recorded. Julius was one month old at the time of his baptism on March 22 or 29, 1863. Reasoning backward to an approximate conception date of June 1862, Marz points out that Lt. Thomas P. Gere, age 19, was stationed at Fort Ridgely at the right time to be Julius’s biological father.

What does a potential son of Lt. Thomas P. Gere have to do with the story of John S. Marsh? Perhaps nothing. If either attribution –that Gere fathered a baby, or that Marsh fathered a baby –is wrong, then any connection between the two is also wrong.

However, we know that commanding officers set the tone for the behavior of their subordinates. And now we also know from primary sources that relationships between officers and Dakota women on the Minnesota frontier were common. So unless Marsh was personally an exception, and unless he imposed and enforced his contrary convictions on those in his command, we can expect his soldiers would have followed his lead. Therefore we can infer from the attitudes and behavior of Marsh’s subordinates, like Sheehan, Gere, and Greer, that Marsh was probably not opposed to the practice of military men taking Dakota women.

This series is over for now because I’ve come to the end of the written sources in my file. But I hope it is the beginning, not the end, of a conversation. Those of us alive today are working in an era where we recognize that humans are multi-dimensional, military heroes not excepted. We are open to “exploring the wrinkles” in stories, as Annette Atkins observes, wrinkles that previous generations of historians seemed intent on “ironing out.”

Many of us are owning up to the limitations of many written historical sources, like Hughes’s claims above, and are opening up to the contributions of oral history. On this subject, Dakota oral tradition tells us that not all relationships between white officers and Dakota women were consensual. In the context of the sharp imbalance of power on the frontier favoring white males, rape and the fear of rape were so common that some Dakota women took physical precautions to thwart any attempt.

We can also expect that if they choose to share their family stories, Sleepy Eyes’s descendants might today be able to fact-check the story about John S. Marsh that Hughes attributed to Nancy McClure. She likely told the story more than once.

As we’ll see, Army officers weren’t the only ones. Coming up on October 4 is a guest post by Walt Bachman examining allegations that Henry Milord, one of the 38 Dakota men executed at Mankato in 1862, was the son of former Governor Henry H. Sibley who ordered the execution.

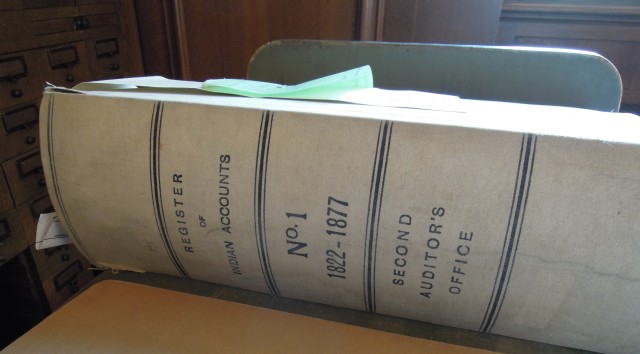

Sources

[1] William Watts Folwell, A History of Minnesota, Volume 2, p. 114 (Minnesota Historical Society, 1924) p. 114. Folwell characterized Marsh as “ignorant and “overconfident” in marching into an ambush at Redwood Ferry.

[2] My transcription of the original held by the Minnesota Historical Society.

[3] Thomas Hughes, Old Traverse des Sioux, p. 128 (Herald Publishing Company, 1929)

[4] William C. Brown to Thomas Hughes March 26, 1928. Thomas Hughes Papers, Southern Minnesota Research Center, Mankato State University, Mankato, MN.

[5] McClure’s letters to Holcombe are in the Return Ira Holcombe Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society.

[6] Joseph R. Brown to Ignatius Donnelly March 12, 1865. Ignatius Donnelly Papers. Microfilm. MHS.

[7] Corinne L. Monjeau-Marz The Dakota Internment at Fort Snelling 1862-64 p. 90 (Prairie Smoke Press, 2005).

Image Credits: Find A Grave and the Minnesota Historical Society. Both via Google Images.