One of the highlights for me of the pre-release weekend for Northern Slave, Black Dakota, was sitting in Gideon and Agnes Pond’s living room talking shop with some of my favorite historians.

You know that tip-of-the-tongue phenomena when you lose a key word at a critical moment and can’t express the thought you meant to articulate?

Well, we historians got onto the subject of tip-of-the-brain phenomena. It happens to all of us. No matter how carefully we try to organize our research, every one of us could share a story about sitting down to write, making a connection that never occurred to us before, and not being able to find the perfect source that flashes to mind to support the connection.

Really not be able to find it. I go down to my file room, kneel in penance before the cabinets and diligently refile everything piled on top — the paper that has come loose or has turned up fresh since my last fetish of can’t-find-something filing. But despite the rituals of restoring order, of vowing that I will refile more often, the missing source eludes me.

A Dakota friend put it this way: We don’t find sources when we’re ready. When they are ready, sources find us.

Last week it happened. A source came back to me, a source I have been waiting on for eight years.

Maybe it took pity on me and figured I’d served my time?

Or maybe it really, really, did not want to be pinned down in note in A Thrilling Narrative and figured now, nine months after the book’s publication, it was safe to show its face.

(This source is too old to know it will go farther on the Internet than in a book.)

*****

One of the themes in my Historical Introduction to the 2012 edition of A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity is Dakota agency –the ways Dakota people appropriated elements of Western culture offered to or imposed upon them, and used them for their own purposes.

You don’t have to look far in the primary literature, like letters written from Dakota country from the late 1830’s through 1862, to see this happening. In fact, it is prominent for the very reason that non-Native observers found it striking–and often, annoying. So they wrote about it.

Unfortunately, the Dakota War of 1862 cast a huge shadow backward obscuring stories like this one. Histories written in the wake of the war –which are most of them –are informed by a chronic sense inevitability: of course Dakota culture would be overrun by white culture; of course Dakota people would be displaced from Minnesota by settlers. The fact that they were made the logic self-evident.

But simply, it is not true.

One way we can see it is to read the letters and other documents Dakota people left us in which they talk about their selective process of adopting elements of white culture. In these documents, Dakota people explain what they were adopting (and not), and often tell us why –their rationale.

Guess what? It isn’t because they admired white people and wanted to be like them. It was because there was something in it for them. It was a means to an end.

This is the case of an 1838 letter written in Dakota at Lac qui Parle by Wambdi Okiya –whose name is often rendered in English as “Eagle Help,” following the translation used by the Dakota missionaries. Ella Deloria, who translated Wambdi Okiya’s letter into English, calls him, “Leagued with the Eagle.”

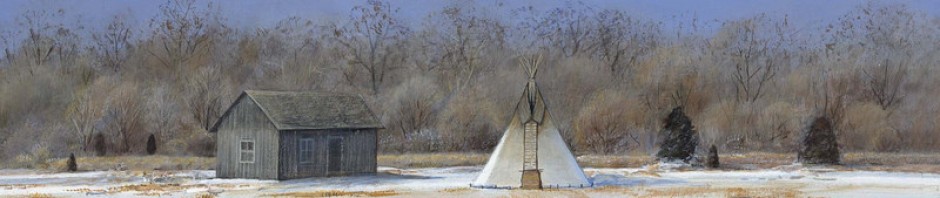

Archeologist’s drawing of Fort Renville, Lac qui Parle, MN, where Wambdi Okiya learned to write in Dakota.

Wambdi Okiya was a member of Joseph Renville’s soldier’s lodge at Lac qui Parle and learned to write Dakota in starting in 1835. Three years later, he explained to his missionary teachers why they hadn’t seen him in a while:

“When you first settled here and taught us writing, and you said you were going to teach us everything, at that time, I alone listened to all you said. But you have never heeded anything I have said to you… I supposed that because you taught me writing, therefore what I asked would be granted, and so I bent every effort towards learning, and lo, from that time to this, I am even worse off…. I want you to be kind to me, but you are not, that is why I haven’t come for a long time. What I wanted was for you to give a little pig to my mother.” –“9th letter Wozupi-wi, Omaka 1838,” Ella Deloria translator, A Thrilling Narrative (2012) p. 10.

“I supposed,” Wambdi Okiya said, “that because you taught me writing, therefore what I asked would be granted….”

But what did he mean? What was the relationship between writing and getting what he wanted? In showing an interest in the missionaries’ teachings, was he developing a relationship that he thought might give him favored status?

When I read this letter for the first time in the beautiful old reading room at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia eight years ago, a different interpretation came to mind. One of the missionaries had written, somewhere, that in the earliest days of the Presbyterian mission, Dakota people believed that written words were uniquely true. As if writing was a mystery that actualized what was recorded.

I couldn’t remember where I had read that. But I was confident I had and considered the other letters written around this period and translated by Deloria with that idea in mind.

Four years later, when I sat down to write the Historical Introduction, I wanted to use Wambdi Okiya’s letter as a snapshot of that place and time because I understood it was a fleeting moment in history, an idea that Dakota people quickly grew disillusioned with. As Wambdi Okiya, said, writing didn’t work as expected.

But by then, the genie was out of the bottle. Dakota people were writing. Some who had learned it gave it up. Others, like Wambdi Okiya, kept writing for the rest of his life.

But in eight years of trying to file-and-wish the mystery source into appearing, it did not show itself. So I used the letter with no annotation on Wambdi Okiya’s supposition, “that because you taught me writing, therefore what I asked would be granted….”

Last week, it came out of hiding. In 1858, Stephen Riggs, writing about Tunkan Wicasta, one of Wambdi Okiya’s fellow soldiers at Lac qui Parle, commented:

“The first winter the mission was commenced, in 1835, Dr. T. S. Williamson taught the young men of Tokadantee, which was occupied by Mr. Renville’s soldiers. The Dakota language was then unwritten. The strange sounds which occurred in it had not then their representatives fully settled upon. There were, of course, no books. Some lessons prepared by hand with types and brush were the best that could be obtained. Slates and pencils were used, but sometimes it was more convenient to make the letters in the ashes. In the Soldiers’ Lodge many young men learned to read and write their own language before they obtained any idea of the benefits of education. Their first notions of these benefits were very inadequate and often very erroneous; they had often been told that “the book did not lie.” Their inference was that everything written must be so. Accordingly, a man sits down and writes, “Medicine Man [Thomas S. Williamson’s name in Dakota], I want you to give me a piece of meat.” The book tells what it was told to tell, and in that way speaks truth. But the Medicine Man can not give the meat and so the book lies. But by degrees book education came to be better understood.”

Why is this source important? Not because it backs up Wambdi Okiya’s letter. But because Wambdi Okiya’s letter backs up Riggs’s story.

Those of us who work in the records left by the Dakota missionaries can be grateful that they documented daily life as it unfurled around them in the decades they interacted with Dakota people. At the same time, we know how culturally-centric was the missionaries’ point of view. They interpreted things as they understood them, which wasn’t necessarily the way they actually were. Certainly not from a Dakota point of view. For that, we need to listen to Dakota sources.